By Bernadette Hoffman

Forgotten Relics exhibit ran from June 2023 to May 2024. Who doesn’t like a mystery? Well, that’s what we have here. This exhibit highlighted a few of our hidden treasures from the museum’s attic.

Some artifacts were given an accession number in 1996 without formal cataloging. There wasn’t a file, information or data accompanying the object. So, I read old director reports, newsletters, and minutes (not all) for any clue as to the provenance or other information regarding the items. I concluded that many of them have been a mystery with questions for years, but I’ve made a few speculations based on the research.

First up, is a “1841 Corset.” This object was found on the collection’s storage room floor between 6-foot-high storage cabinets. In 2015, I was cleaning the tops of the cabinets and bagging specimens when I noticed it below. With it was a handmade coverlet but that’s another story. Evidently, it had fallen off from one of the cabinets and laid there for who knows how long. When I discovered it, there was a partial tag with what could have been Franklin’s handwriting and an accession tag from 1996. As stated above, no information could be found on it. I did find a display label among other museum labels and tags. It must have been on exhibit at one time. The item didn’t look like a corset to me. I reached out to a textile and fashion museum in the UK for possible identification. The Victoria & Albert Museum of London stated that this object is not a corset but a back support or similar dating late 1800’s to early 1900’s. This posture corrector or brace might have been called a corset during that era and based on the size most likely it’s for a woman. It appears to have a missing cord or perhaps a corset-like front piece to pull the hip stays in place. It’s made of canvas material, leather, metal buttons and stays. A velour material covers the hip stays, and the number 8 is engraved on both ends. Perhaps it’s a size number?

#2 – Reuel Pember’s 1852 Account Book

This account book has been in the museum’s storage room tucked inside a metal map cabinet. It’s like a paper bag material with sheets of paper folded and stitched together with thread. There’s no information as to how it arrived to the attic. We can assume it belonged to Franklin following his father’s death in 1873. However, besides having Reuel’s name numerous times on the document’s cover, there’s the name of Abraham Rogers, Jr., Branford, New Haven County, CT. Who was Abraham? Research informs us that there were three Abraham Rogers in Branford, CT. One born in 1749 with two “Jr’s” born in 1783 and 1813. Why is Abraham’s name on this document? The handwriting is clearly different than that of Reuel’s. Lucky for the Pember that I have an ancestry account in which to research people of the past.

This account book has been in the museum’s storage room tucked inside a metal map cabinet. It’s like a paper bag material with sheets of paper folded and stitched together with thread. There’s no information as to how it arrived to the attic. We can assume it belonged to Franklin following his father’s death in 1873. However, besides having Reuel’s name numerous times on the document’s cover, there’s the name of Abraham Rogers, Jr., Branford, New Haven County, CT. Who was Abraham? Research informs us that there were three Abraham Rogers in Branford, CT. One born in 1749 with two “Jr’s” born in 1783 and 1813. Why is Abraham’s name on this document? The handwriting is clearly different than that of Reuel’s. Lucky for the Pember that I have an ancestry account in which to research people of the past.

The booklet is a daily account in the life of Reuel (pronounced Ruw-ahl; Hebrew origin “Friend of God”) and begins on January 1, 1852. It’s very difficult to read and not only because it’s 1800’s style script but there’s no punctuation and the sentences run together. By the way, I have it scanned. So, should anyone feel like contributing to the Pember, we’d love to have you volunteer your time to transcribing it. Not only was Reuel (1810-1873) a farmer in his lifetime, but he was Justice of the Peace, as well.

Reuel writes “the 16 L.D. Pember and wife was here. Sold him two cows. Took a note against Samuel Nelson forty gallons first day of April next due”

Reuel writes “the 16 L.D. Pember and wife was here. Sold him two cows. Took a note against Samuel Nelson forty gallons first day of April next due”

Why would Reuel mention his brother, Lorenzo Dow, (2nd wife Mariam) as L.D. Pember and not as my brother Lorenzo and Mariam?

The 29- Done chores the 30 went to Argile took oath of office as a Justice of the Peace for 7 years from the first day of Jan 1853

The 29- Done chores the 30 went to Argile took oath of office as a Justice of the Peace for 7 years from the first day of Jan 1853

This is when Reuel becomes a JOP.

Fun Fact:

The 1850 Agricultural census lists Reuel (#16) as owning 100 acres of land, 2 horses, 5 milk cows, 100 sheep, and 3 pigs with a value of $487. He had 330 pounds of wood, 1200 Irish potatoes, $50 value of orchard, 700 pounds of butter and 30 tons of hay. Wow!

BTW, David Wood, Ellen’s father (#34) on the census owned 10,500 pounds of cheese! That’s a lot of cheese!

Did you know that we have an 1853 Washington County Map? Here’s a scanned pic of where Reuel and David Wood lived during that time. We have these poster maps for sale in the library for $8. The original (5’x6′) is in the collection’s storage room.

#3 – Decorative Cow Horn – This object was stored in a file cabinet drawer with other oddities located in the attic. I believe the tip is filled with plaster as it’s heavy. The horn has a sawtooth patterned edge, double-jack chain, and old cup hooks. At first glance, the decorative trim appears to be metal, but it’s a die-cut embossed foil paper trim. Dresden trims have been made in Germany on machines for over 200 years. Based on research, I believe this horn is from the Art Deco (1919-1939) era.

#4 – Pember Library & Museum Accessions Book – This accession book has been stored in a map cabinet drawer in the collection’s storage room. It’s volume two dating February 6, 1914 to June 3, 1924 with books accessioned from #5,001 to 10,000. You may notice that F.T. Pember donated a book on Woodpeckers (#5002). Did you know that Baker & Taylor is one of the library’s book sources today? I searched for volume one but couldn’t find it.

#5 – Civil War era Horse Breast Collar – This is my favorite relic. This horse breast collar has been in the collection’s storage room probably since it was built in 1985 and before that in the open space of the attic for years. It was accessioned in 1996 but not formally cataloged until 2017. The collar was in poor shape and has recently been conditioned with Pecard antique leather dressing in hopes of preserving it. The brass rosettes have been cleaned and polished. There is a possibility that a brass heart was once present the would have fitted over the leather one in the center plate. We have included a brass heart reproduction for the exhibit.

Breast collars were used in the American Revolution, War of 1812 and through the 1850’s. However, for the Civil War (1861-1865) it was not standard issue tack for the Cavalry. They were also used in the Spanish-American War of 1898.

Although not standard issue in the Civil War, officers were known to purchase their own tack. Typical breast collars would have a martingale strap that went between the horse’s front legs. This collar has a decorative tassel with no evidence of a pre-existing strap. However, the buckles have been compared with another Civil War breast collar and they are nearly identical. The comparative breast collar has rosettes and a centered brass heart. You can view this gorgeous breast collar below (courtesy of Bobinwmass of the Civil War Talk Forum).

A YouTube video titled “Did the Cavalry use Breast Collars?” by the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry is very interesting and a must watch!

Provenance theories: The collar was crafted before or during the Civil War based on its design and was gifted to the museum at any time. OR maybe… it’s from Franklin Pember’s first cousin, Reuel Pember, who was a harness maker in Nebraska from 1886-1920. In addition to harnesses, he made collars as I found his business ads in old newspapers. It’s possible that he made this collar and gave it to Franklin when he came to visit between 1910-1919 (per the Pember genealogy book). OR maybe it belonged to Reuel’s father who served and died in the Civil War.

We may never know!

The collar was conditioned with six treatments over the span of two months. It needs additional treatments because the leather on the left had gotten wet at one time and was extremely stiff and warped. There was also serious signs of dry rot. In order for it to be around for years to come, periodical treatments will need to be done. The tassel’s leather strap is extremely fragile even since being treated.

#6 – Jane McCrea Wood Fragment – Oh boy, this relic proved to be an exciting research project. I found it in 2016 among botany specimens. At that time I accessioned and cataloged it with nothing other than a photo and what was clearly visible since I couldn’t find any relevant information. I did a brief research and read an article that Jane’s remains were moved in 1853 from one grave to her final resting place and speculated that perhaps this piece of wood was from her casket. I also thought it could have been from her house. Then it was tucked away into storage. For this exhibit I began researching her again and particularly the date. I found that one article had her moved in 1853 while several others noted 1852.

Jane McCrea was born in New Jersey and met her death at the hands of Native Americans on July 27, 1777 in Fort Edward, NY. She was between the age of 17 and 24 as records are not clear. There are several stories as to how she died and is buried in the Union Cemetery of Fort Edward. You can find a ton of articles about her online.

Research discovered that the tree which stood where Jane was killed died in 1849 and in 1853, the property owner, George Harvey felled the tree. (See our 1853 Washington County Map scan) He then had it made into canes and curious boxes or snuff boxes as articles have explained by J.M. Burdick of Ft. Ann. If you look at the ad in the NY Times of August 17, 1853, these items were sold at the Crystal Palace in NY City along with a few other locations. It mentions that each item would be inscribed as evidence of authenticity. Newspaper notices of Mr. Harvey’s intent began in March. He placed this ad in the NY Times from August 5 through September 2. George Harvey was a merchant in 1850 and bank president for Farmers Bank in 1860. The New York Crystal Palace was an exhibition building constructed for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (World’s Fair) in New York City in 1853, which was under the presidency of the mayor Jacob Aaron Westervelt. The building stood on a site behind the Croton Distributing Reservoir in what is now Bryant Park in Manhattan. In October 1858, the Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire.

Could this piece of wood be from one of his boxes or a chip from the tree and how did it end up at the Museum?

One can find Jane McCrea historic markers in Ft. Edward, NY with online maps and information. I visited and snapped a few photos of them.

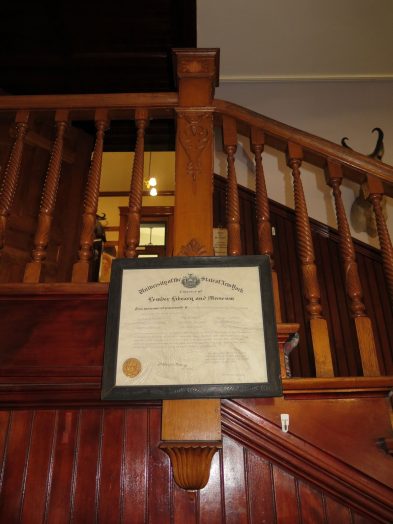

#7 – Cast Iron Ornate Flush Bolt Door Latch – This latch is not as exciting as the McCrea wood fragment but nonetheless still interesting. I found it on a attic shelf having no clue as to what it was or where it came from. We are lucky with today’s technology that a photo research can be done on the Internet. Research showed that it is c1890 and used right here at the Pember. It was installed on the museum’s door located on the stair landing in 1908/1909 and was removed and broken when carpet was installed for the library/museum stairs. Since that was before my time, I don’t know the year. I found an identical one on the web and you can see what the broken half of the latch looked like. At one time it had a bronze finish.

#8 – Oak Carved Corbels 1908/1909 (for lack of a better description) – These items were found in the northeast corner of the attic on the floor covered in years of dust. Sometimes they are called wall brackets but they are a decorative piece of the stair’s newels in the library. Not a post cap but are located at the bottom of the newells. Are these spares or were they used somewhere else?

#9 – Revolutionary War era Saddle Pistol Holders – This pair of saddle holsters have been in the collection’s storage room. Only a note of “pre-civil war” was found in the files. The holsters were in poor shape and have recently been treated with Pecard antique leather dressing in hopes of preserving them. The brass end caps have been cleaned and polished. Saddle Holsters were either attached to the saddle horn through a hole in the seat which is the connecting piece between the holsters or strapped to the saddle. They were also called pommel holsters. The small pockets on the holster’s front were used to store cartridges. Research found a pair sold at auction was dated c1780 that looked similar to ours with four cartridge pockets and metal tips.

#10 – Tramp Art Box – This box has been stored in the collection’s storage room and it’s provenance is unknown. It’s comprised of carved chips from cigar boxes. The Tramp Art period ranged from 1870-1940. There is writing on the bottom of the box but we’ve been unable to read it other than Granville, Washington, NY. The bottom of the inside tray has a 3-line factory identification which puts the cigar box’s date from 1883-1910 (the Golden Age of Cigars). It is stamped:

Factory No. 262

9th DIST. P.A.

50

Our last forgotten relic is a 14×17 black embossed wood picture frame that was found in the northeast portion of the attic faced down in dust and cobwebs. The glass was missing. The age of the frame and provenance is unknown. I lightly cleaned it and added a piece of plexiglass for it to be used as our exhibit sign. It’s a beautiful piece with leaves and flowers or berries pattern.